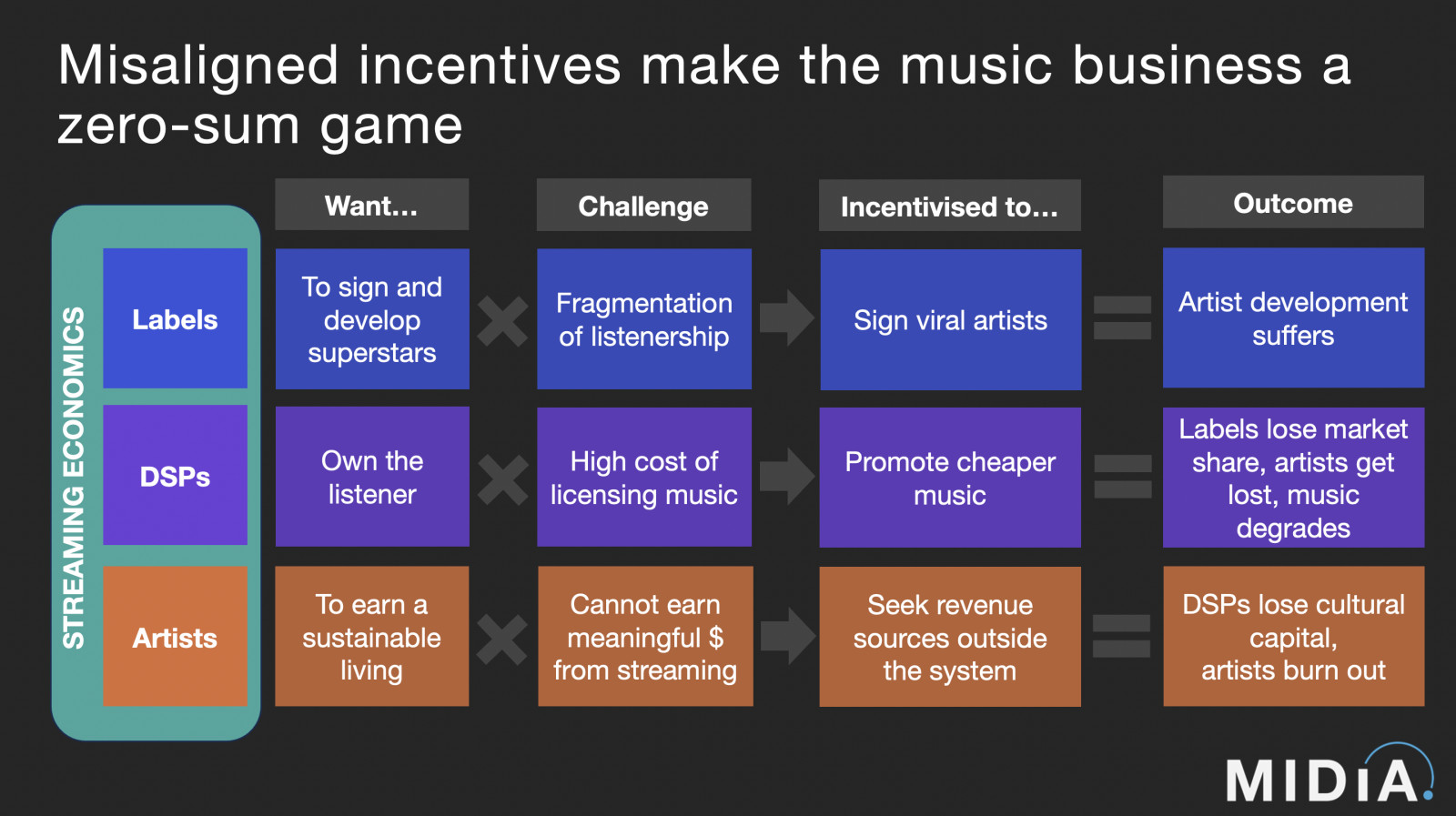

Misaligned incentives make the music business a zero-sum game

“Pop Stars Aren’t Popping Like They Used To”, Billboard’s Elias Leight writes in a recent article, in which record label executives stress over the struggle to break new artists. The article (or at least, the headline) stirred up a storm on Twitter — ahem, X — last week, where many users took the opportunity to slam record labels’ misguided focus on virality. The feeling was unanimous: cue the tiny violins.

However, the reality is not so black-and-white. Record labels are far from the only ones impacted by the fragmentation of listenership. It is becoming harder for everyone to break through the noise and even harder to create what we used to think of as mainstream hits. Labels are acting in response to the incentives that streaming created — sure, incentives that labels helped shape, but likely not with the consequences they intended.

The wider problem is that nobody’s incentives are really aligned. This has turned the music business into a zero-sum game.

Misaligned incentives

Labels are incentivised to grow market share at any cost

Under the pro-rata streaming model, where scale is the only thing that matters, labels are incentivised to grow their market share by any means possible. The reality is that labels can see more upside by signing a viral hit to a singles deal, than spending years developing an artist who may or may not be successful. As listenership grows ever more fragmented, labels are ever more incentivised to cling to anything that does get everyone listening at once. The result, as X users widely pointed out, is that artist development is suffering.

DSPs are incentivised to promote cheaper music

Featured Report

Music catalogue market 2.0 Bringing yesterday’s hits into the business of tomorrow

The music catalogue acquisition market bounced back from a slightly cooled 2023 with a new fever in 2024. What is being bought is changing, however, as investors look to diversify their portfolios and uncover new growth pockets in an increasingly crowded market.

Find out more…DSPs want to own the listener. Their challenge is that licensing music is expensive, especially major label repertoire. Spotify famously pays back nearly 70% of every dollar it earns from music back to rightsholders. It is in DSPs’ best interest, then, that consumers listen to more, cheaper music, like so-called “royalty-free” music, mood music, and generative AI music. The more this happens, the more DSPs gain leverage — but the quality of music on these services degrades, and both labels and artists lose out.

Artists are incentivised to build outside of the system

As more artists realise they cannot earn meaningful revenue from streaming, many are de-prioritising DSPs in their strategies. Of course they are still distributing their music to streaming, but they are concentrating promotional and monetisation efforts in other areas, like live shows, merchandise, brand deals, YouTube subscribers, etc. This reduces the cultural capital of streaming, because DSPs are no longer the spaces where music fandom and culture happen — they are merely the pipes for consumption. Moreover, in pursuit of all these revenue sources, many artists simply burn out.

What’s left?

If labels lose revenue, DSPs lose cultural capital, artist development suffers, and artists burn out, what are we left with? A new generation of artists who lack the support systems and monetisation pathways to get started in the first place, let alone break big. Yes, this is massively oversimplifying things. But it is hard to see a path forward in a system where every stakeholder’s gain is another’s loss. Unless (or until) streaming economics fundamentally change, stakeholders will have to go against the market’s guiding incentives to escape this zero-sum game.

Finding a way out

Labels are measuring the success of today’s artists against that of artists who broke big before the market became so fragmented. We may have fewer globally-recognisable icons today, but we have more mid-tier stars with devoted followings. It is entirely possible for an artist like Carly Rae Jepsen to be the biggest star on earth for a certain corner of the internet, but totally unheard of in another. Just ask 100 gecs, a duo with 1.7 million monthly Spotify listeners whose fans are bonded by the fact that outsiders do not really “get it”. We need a new definition for what it means to “break” an artist — and a way to do so without breaking artists.

In her recent Embedded piece “Going viral sucks (even more now)”, writer Kate Lindsay explained how, by relentlessly focusing on discovery, TikTok’s algorithm can push creators away from their audience. This is in addition to all the other common side effects of virality: exhaustion, toxic comments, and general unpreparedness. Of course, TikTok has opened doors for many grateful artists. But why did we decide that skyrocketing to instant, fleeting internet fame is the best way to kick-start a music career?

Maybe managers should really be doing the opposite: ensuring that early-stage artists do not have viral moments (yet), so they can focus on developing their music before opening themselves up to the entirety of the internet. This is an opportunity for a brave company or executive(s) to focus specifically on artist development, even though it would mean going against the incentives guiding today’s industry. It may be no surprise that the artists that are still “breaking”, in the traditional sense, come from the K-pop world — where labels like HYBE spend literal years training groups before they release any music, disregarding the almighty algorithm.

Everything is coming full-circle: labels went from developing unknown artists before releasing music, to, in recent years, signing artists only after they have already “broken”. Now, the pendulum is swinging back — not all the way, but perhaps landing somewhere in the middle.

There are comments on this post join the discussion.